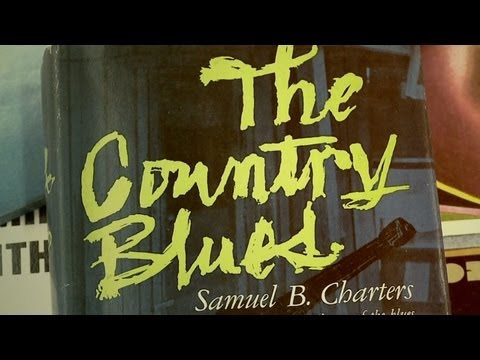

His 1959 book The Country Blues was as important as Harry Smith's anthology American Folk Music had been earlier the same decade - because it inspired people to action: to the seeking out of blues giants of the pre-WWII age. He also played a significant part in the story of creating album releases of Blind Willie McTell's work.

I interviewed Sam Charters by telephone when I was researching Hand Me My Travelin' Shoes, and he was friendly, helpful, informative and lively-minded. This is from my book, and is looking at 1956 (just when Willie is making his last recordings in Atlanta):

At the same time, 375 miles away in Memphis, Tennessee,

another enthusiast, a Pittsburgh-born 30-year-old called Samuel Barclay

Charters, is traveling around with his first wife, Mary Lange, and recording

old blues singers a bit more systematically.

Anyone else

with a keen interest in music who finds themselves in Memphis in 1956 is in the

thrall of rock’n’roll. Memphis is the

place to be in 1956. Here is the home of the wondrous Sun Studios, where Sam

Phillips has just been producing Elvis Presley’s revolutionary first records,

in one small, dark room that is now also capturing on tape the early golden

exuberance of Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, and more. In the same

room Phillips has also been commissioning pioneering modern electric blues

records since 1951, when he had glued the little white baffle tiles up on the

walls and ceiling himself to make the room a studio. Howlin Wolf had started

here, right then and there. Phillips said later, “When I heard him, I said,

‘This is for me. This is where the soul of man never dies.’”

But that’s

not how Samuel B. Charters feels. He’s not in Memphis for this stuff at all. He

doesn’t even notice it. Decades later, when I interview him, I say “You were in

Memphis in 1956?! What a wonderful time to be there!” and he replies: “It

really was, yeah. They were all there,”

- and the people he means are old, pre-war blues singers,

and street musicians from Memphis jug bands: the very people that everyone else

in Memphis has forgotten.

These are the people he finds and records:

“Gus Cannon and Will Shade and everybody with the jug bands.” Gus Cannon and

friends, under various names but mostly as Cannon’s Jug Stompers, had done a

slew of recordings between 1927 and 1930, and never been back in a studio

since. Will Shade had led the rival outfit the Memphis Jug Band, and they had

recorded prolifically between 1927 and 1934.

When

Charters finds them, and records them again for the first time in over twenty

years, it makes him realise something simple and powerful: “the revelation that

these people weren’t from another planet, they were part of our life and some

of them were still alive.”

Three years

later, in 1959, Sam and Mary are divorced and in March Sam marries his second

wife, Ann Danberg, whom he’s met in music classes at the University of

California years earlier, and who will later write the first biography of Jack

Kerouac and edit his letters. Sam and Ann Charters live in a basement apartment

in Brooklyn, but that fall they’ve driven all the way across the States to stay

with Ann’s parents in California before embarking on a year-long trip to

Europe.

That

November, the New York publisher Rinehart publishes Sam Charters’ book, which

is called The Country Blues - and

it proves to be one of those rare books that actually makes something happen

out in the world. Effectively it kicks off the blues revival that becomes a

shaping force within the whole burgeoning scene that encompasses the New Left,

the civil rights movement, the Greenwich Village folk phenomenon, the rise of

Bob Dylan and more.

The blues

that Charters draws to people’s attention, and which he invents the phrase

“country blues” to describe, is neither the vaudeville-jazz sort they’ve heard

by Bessie Smith nor the electric post-war blues they’ve heard by Muddy Waters

and Sonny Boy Williamson and Howlin’ Wolf. It is pre-war, mostly downhome,

southern and unamplified, and as richly diverse as life under the sea.

On the LP

that he issues alongside the book, Charters’ compilation of a few of these old

records includes an elegant but restless, exhilarating track made in 1928,

‘Statesboro Blues’, written and recorded by Blind Willie McTell. (Statesboro,

Georgia, is the quirky town Willie grew up in, 49 miles northwest of Savannah.)

The LP is, in effect, a bootleg, since the companies that really own the rights

and the masters to these recordings have no interest whatever in releasing them

officially while at the same time their procedures for allowing others to lease

them make it prohibitive for any blues enthusiast to compile such an album

legitimately. Charters deals with this matter head-on in his sleevenotes to

this “bootleg” LP.

He has

acquired the mint-condition 78rpm record of Willie’s ‘Statesboro Blues’ that is

copied onto his LP from a cache of ancient but never-played Victor Records

found somewhere in New York State by another key figure on the scene at the

time, Len Kunstadt, who edits the tiny, amateur-looking magazine Record Research (which Charters writes

for) and acts as the manager of one of the known surviving grandes dames of the

pre-war blues, the redoubtable Victoria Spivey, who now lives in Brooklyn and

is just about to re-emerge from semi-retirement. Len will also prove to be her

last husband.

The 78s that

Len Kunstadt finds are of course regarded as riches, among the interested few,

but their monetary value is derisory, and will be slow to rise. Paul Garon,

writer and blues-specialist Chicago bookstore owner, recalls the prices when,

back here when the 1950s were just giving way to the ’60s, some Robert Johnson

78s were put up for auction by another enthusiast, Chris Strachwitz: “I

stretched my budget enormously and bid $2.50 each. I lost. When I saw Chris

later that year, I bemoaned losing the RJs (he was auctioning three of them),

and he said, ‘Oh, you lost by a mile. They went for $7.50 each!’” In

December 2004 a Robert Johnson 78rpm of ‘Come On In My Kitchen’ coupled with

‘They’re Red Hot’, recorded in late 1936 and issued on the Vocalion label soon afterwards,

in only fair condition, sold on eBay for $4,495.

When his book comes out on 5 November 1959, Charters is

working for Minke’s Closet Shop in Beverly Hills, putting up wall cupboards for

the Hollywood actress Cyd Charisse. In his lunch hour he stands around in a

little Beverly Hills bookstore, holding a copy of his own book so that people

might see the photograph on the back and realise that he’s the man who wrote

it.

Charters’

book doesn’t impress everybody. He pips to the post the rather more precise and

thorough blues scholar and British architect Paul Oliver, whose book Blues Fell This Morning would arrive in

1960, as would American jazz writer Frederic Ramsey’s Been Here and Gone, a richly photo-loaded account of travels

through the 1950s South in search “of what might still remain of an original,

authentic African American musical tradition”.

There is

much carping too from some of those who feel they already know about all this

music but haven’t troubled to write books about it. They feel that despite all

the fieldwork Charters has done, in Alabama, New Orleans, Memphis and even the

Bahamas, he doesn’t have a proper folklorist’s interest in “the tradition”, but

rather has the sort of flighty interest in “originality” and “creativity” that

is just what you might expect from a literary person with an inclination

towards Beat poetry.

Charters’

critics also complain that there are far richer seams of pre-war blues than

those he looks at and that he gives too much attention to lightweight hokum at

the expense of heavier, superior material born in the Mississippi delta.

Actually

this remains the main divide in the world of blues appreciation -

among the enthusiasts who start up small record-companies, the

fieldworkers and scholars who persuade the subject into academic legitimacy and

the writers on small magazines. Most of the white post-war champions of this

black pre-war music are predisposed to find heaviest best. Dark, smouldering,

Mississippi blues good; lighter, cheerful, South-Eastern blues much less good.

When we

come to ask how and when, after his death, Blind Willie McTell becomes famous,

we find that the answer is slowly and moderately - and

part of the reason is precisely because he isn’t Mississippi, he isn’t raw and

dark.

In any

case, Sam Charters’ The Country Blues spreads

the news of this music to a larger number of people. It also prompts many a

young urban white to take a trip down to the Deep South in search of the old

rural blacks whose records from decades earlier are just beginning to be issued

for the first time on 33rpm vinyl by like-minded young enthusiasts -

records that reveal to them this other, more magical music universe.

Some

successes are scored. The frail, eerie recordings of Skip James from 1931 are

all people have to go on, but he is found, alive, back where he’d started from,

in a tiny town in Mississippi. He will appear like a ghost on stage at the

Newport Folk Festival in 1964, having never recorded in the intervening 33

years. Mississippi John Hurt, a kind and gentle man whose last foray into a

recording studio was in 1928, is descended upon similarly and plucked back into

the world of public performance - a world where that public has changed out of

all recognition.

Son House,

another once-towering figure, is rediscovered, not in a shack in a field in

Mississippi but in a rough part of Rochester, New York - and

he too finds himself up on stage for the first time in decades, playing to

young white audiences in the coffee-houses of Greenwich Village and Boston,

Philadelphia and Washington D.C..

Blind

Willie McTell is one of those sought out

- but too late. Nobody knows it

yet but he is already dead. He dies eleven weeks and a day before the release

of his ‘Statesboro Blues’ on the Sam Charters LP.

No comments:

Post a Comment